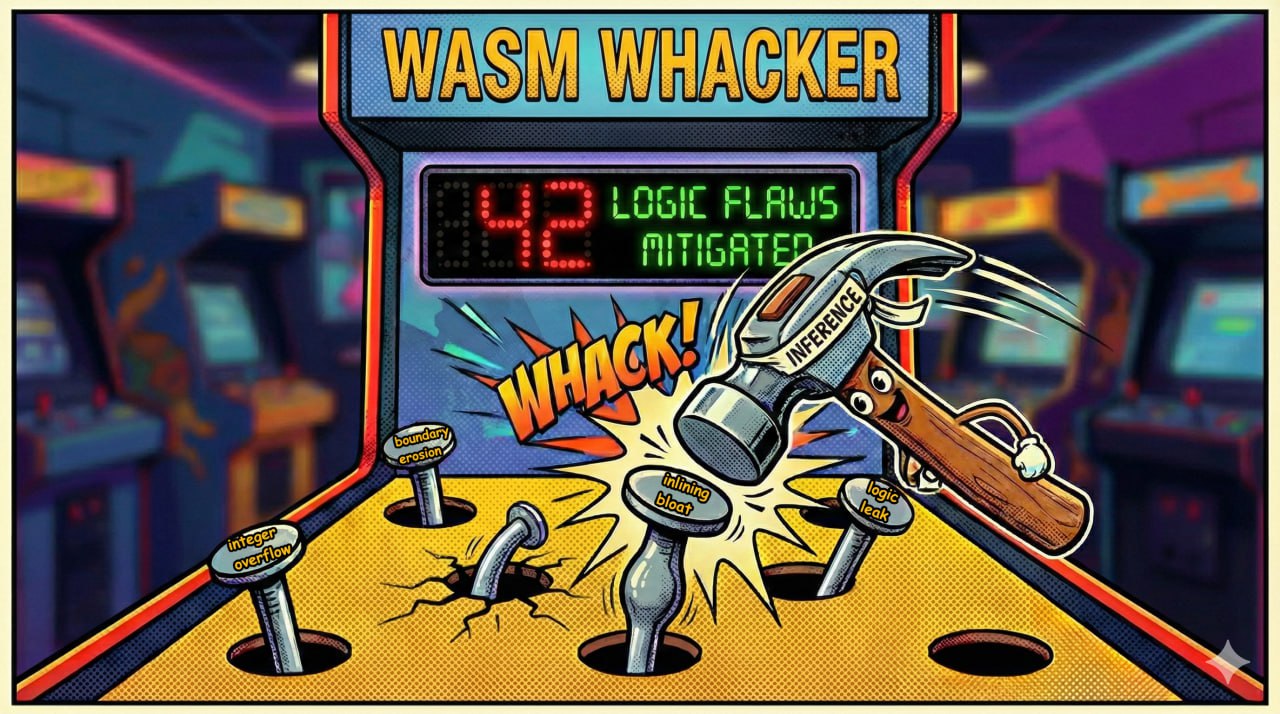

A Hammer in Search of Nails

In the process of developing a new tool, a reasonable need inevitably arises at some point to test it outside of one's own workshop, in the uncontrolled environment of the real world. Our innovative framework for specifying and verifying programs known as Inference is reaching exactly this stage - calling us as its creators to try this futuristic hammer on every nail they encounter. However, since there are only 24 hours in a day and the number of projects on GitHub to which formal methods could theoretically be applied is substantially larger than makes sense to count, one has to somehow filter the potential territory of work.

For obvious reasons, when discussing ways to improve software reliability, it is sensible to focus on projects with a higher cost of error. Blockchain platforms inevitably end up at the top of the list because damage from emergency situations in the crypto industry almost always has a direct monetary valuation, the average value of which continues to grow. A second natural selection criterion is the technology stack: the automation of the WebAssembly standard became the experimental testing ground for our technology. Therefore, a short list of nails suitable for our hammer at the current stage can be composed of blockchain platforms targeting WebAssembly for cost-bearing purposes. Within this article, we will touch upon three such projects: Polkadot Substrate, Stellar Soroban, and Arbitrum Stylus.

When looking at this trio from a distance, a certain superficial kinship catches the eye as they all use Rust as one of the primary languages for contract development, and the WebAssembly platform is the foundation of their runtime. However, upon closer examination through the lens of formal verifiability, fundamental architectural differences begin to manifest, which I would like to discuss here.

Polkadot Substrate

The framework authored by the Parity Technologies represents a continuously expanding set of ready-made solutions for core crypto-financial accounting patterns, organized as a collection of modules with a special structure (pallets) in the Rust language. A high-tech build system allows these modules to be combined in any way, thereby producing new versions of the runtime containing only the functionality necessary for each individual case. The main architectural principles of the collection can be formulated as follows:

- The pallet as a universal unit of integration. Any functionality that a blockchain developer might need, from individual aspects of infrastructure to popular business logic patterns, is provided in the form of uniformly connected modules.

- Active use of the Rust type system and advanced metaprogramming tools in the horizontal interaction of modules for the most comfortable and safe code reuse.

- Great attention to runtime performance optimization using the most powerful techniques. Aggressive inlining at the Link Time Optimization (LTO) stage is the default setting when building the final binary.

At first, it might seem that the qualities listed above are a hymn of praise, but unfortunately, such an architecture also has a dark side that inevitably follows from the same combination of factors that create its advantages. In the shadow of these benefits, alas, hide problems capable of effectively putting an end to the feasibility of an entire class of methods for formally ensuring the reliability of the system both as a whole and in parts.

When discussing the methodological benchmark of formal methods, which is the verification of executable binary modules at the level of platform semantics, any sufficiently large codebase subject to verification requires a series of properties that programmers usually rarely worry about. These requirements arise in connection with the fundamental principles of reasoning about algorithms and are, in fact, mandatory:

- Complex systems are not verifiable in their entirety. The only practical way to verify complex systems consists of breaking them down and specifying subsystems that are as isolated from each other as possible, which are then verified independently of each other.

- The total verification costs grow proportionally to the square of the number of subsystems sharing the common state space. Without clearly defined boundaries of “domains” whose integrity is ensured at the platform level, verification must be based on the presumption of mutual influence of all on all.

- Reusing judgments about algorithm properties is much harder than reusing the algorithms themselves. Monomorphization and inlining are effectively free for the developer and end user but are very costly in the context of formal verification because every copy of the code produced by these procedures becomes a separate target requiring independent coverage.

In this light, it suddenly becomes apparent that the FRAME architecture, unfortunately, chooses to complicate the task of formal verification at virtually every turn. Yes, at the source code level, the pallet system exudes flexibility, modularity, and ease of use. However, full formal verification of source code in Rust will remain a utopian dream for a long time to come (simply due to the lack of an official specification of its semantics), while at the level of executable binaries, the picture becomes much bleaker.

The central problem is that all structural boundaries between source code modules are completely erased by the compilation process at a fairly early stage. In fact, the ability to use macro definitions from one pallet in another erodes them even at the preprocessing stage. If one disassembles the final result, for example the official Polkadot runtime, the result will be a single monolithic module with over two million instructions, where only a very rare function can be unambiguously assigned to a specific pallet. Worse still, at the center of this artifact will lie a single function spanning hundred thousand lines, generated by the automatic inlining of a myriad of completely heterogeneous pieces of code from all corners of the project directly into the body of the central event dispatcher.

Unfortunately, the only thing any formal verification engineer can do when faced with such a task of work is to throw up their hands and give up, because at this point specifying and proving correctness in such conditions is technologically nearly impossible and economically absurd. Even if by some miracle one could create a comprehensive and rigorously proven specification for a specific version of the Polkadot runtime, this achievement would be completely non-transferable not only to its derivative forks with a different composition of included pallets but even to subsequent versions of Polkadot itself. Furthermore, considering the lack of reliable determinism in the Rust build process even with Docker sandboxing, it would sometimes be enough to simply recompile the binary on another machine to invalidate it; due to thread racing (apparently) during parallel compilation, the address space of shared memory and the ordinal indexing of functions are mixed up completely freely.

Is it possible to somehow compensate for the above problems with little effort without performing a radical revision of the architecture? This is a difficult question considering how rapidly progress moves in this area. It is possible that in just a few years, verification automation using LLMs will allow us to simply throw a rack of graphics cards at all the scaling problems. But until then, I fear the outlook is disappointing: attempts to obtain formal confirmation of the correctness of any runtime that inherits the Polkadot code base, in the form in which it is deployed and executed seem impractical. This should not, however, deter its users and developers from applying formal methods to improve reliability on a smaller scale. For example, non-trivial arithmetic in important functions can be verified at the pseudocode level, and the isolation of contracts in separate wasm modules allows us to consider verification at the assembler level, at least for them.

Stellar Soroban

When encountering this platform after Substrate, the first thing that catches the eye is its radical minimalism. The dedicated core of the cryptographic ledger contains only 500 thousand lines of a very orthodox subset of C/C++ code. There are no excesses, only the basic functionality of the network protocol and an algorithm that implements distributed consensus. There are no optional components, as every function is necessary for the system to work. Metaprogramming and polymorphism are rarely used, and classic procedural code operates straightforwardly on explicitly defined data structures.

"That's how our grandfathers and great-grandfathers wrote code"

you might joke, and you would not be far from the truth. Indeed, with the exception of the progress of the TCP/IP stack and a slight artistic exaggeration, the Stellar core could have been compiled for a mainframe from the last millennium using a compiler from the mid-90s.

However, it would be a big mistake to mistake this minimalism for archaism. Some development methodologies change little over the years for the same reason that crocodiles do not evolve, because they are perfectly adapted to their ecological niche. As paradoxical as it may sound, if you are planning a system that is subject to formal verification at the level of an executable binary, the classic procedural style of straightforward operation with clearly defined data structures is your best (and, as the system grows, your only) chance.

The fact is that this seemingly archaic development method is optimized from the point of view of the main parameter affecting the verifiability of the system as a whole, which is the structural distance between the source code and the assembly listing. By consciously giving up the comfort and flexibility that modern programmers are used to, we receive in exchange an invaluable advantage for reasoning about algorithms. The ability to juxtapose, line by line, the statements and expressions of the language used by the programmer with the compact groups of machine instructions that come out of the assembly process. The clarity of the developer's thought, which is completely lost when minced by additional layers of abstraction in meat grinder of more sophisticated modern compiler, remains relatively intact through the transparent compilation process of orthodox C/C++ and can be read by a trained eye, often even after applying fairly aggressive optimization techniques.

At the same time, Stellar developers do not force end users to adhere to such strict asceticism when developing Soroban contracts deployed on their blockchain. Yes, when communicating with the external environment (the platform and other contracts), programmers have to limit themselves to the classic monomorphic Foreign Function Interface (FFI) with a small list of permitted base types, which, from the point of view of verification, is again a significant advantage. However, the official SDK is written in Rust, so within the contract itself, everyone is free to build arbitrarily complex abstractions without significant obstacles. At the same time, thanks to the isolated WebAssembly execution environment and the absence of shared state with the infrastructure and other contracts, programmers do not have to worry about breaking any reliability guarantees provided by the platform.

It is not entirely fair to directly compare the Polkadot and Stellar platforms, since the former, in addition to the basic blockchain infrastructure, offers users a wide range of ready-made engineering solutions for all occasions, while the latter clearly disclaims responsibility for all business logic issues. Typically, functionality that is just a simple inclusion in Substrate's ready-made pallets is expected to be implemented by the user themselves in Soroban in the form of contracts based on examples from a separate repository. However, it is difficult not to notice how strongly architectural decisions influence the prospects for formal verification. Yes, 500k lines of C/C++ is also a lot, and full verification of the project would likely stand alongside unique achievements like seL4 and CompCert, but the success of this endeavor is at least conceivable!

Arbitrum Stylus

The third project that caught our attention occupies an intermediate position, in a sense, in terms of potential verifiability between the polar opposite approaches of the first two. To understand its verifiability, one must distinguish between the Nitro host and the Stylus execution environment. The underlying node software (Nitro) is primarily written in Go, a choice driven by its origin as a fork of the Ethereum Geth client. While Go provides excellent concurrency for handling network interactions and sequencing, it does indeed introduce a complex runtime and garbage collection layer into the node’s infrastructure.

Go which is slightly less close to assembly language than the classic C/C++ pair due to its more complex runtime with native support for lightweight threads, but does not rely as heavily on advanced metaprogramming tools and complex typing as Rust. Due to the apparently greater expressiveness of the concurrent style of Go routines when handling network interactions, Nitro core is even more compact than Stellar - approximately 200k lines together with the Rust glue. It should be noted, however, that the central advantage of this platform which is the seamless interoperability with the Ethereum network, is achieved by including a full-scale implementation of the corresponding protocol in Go, adding another 400k lines to the project.

It should also be understood that when assessing the complexity of formal verification at the level of executable binaries, not all lines are created equal - the expressive power of Go is unfortunately not free. The runtime infrastructure that provides native concurrency not only becomes an additional target for verification with fairly complex semantics, but also creates an additional layer of abstraction between the source code and the assembly listing, making it harder to directly align.

Another architectural decision that somewhat complicates verification is the choice of the EVM distributed ledger as the persistence model. The motivation here is quite clear since interoperability with the most popular smart contract platform at the moment is obviously a huge advantage. Unfortunately, this cryptographic ledger design seems to be popular more for historical reasons than architectural merits because it requires a certain level of intermixing between contract business logic and the consensus mechanism that could have been avoided. To see how much this complicates things, it is enough to look at the implementation of persistence without regard to legacy in Stellar for comparison. There, the contract, completely isolated with its own data, is not concerned with indexing its state in the global trie at all. With this approach, the business logic is strictly separated from all infrastructure issues at the level of isolation in WebAssembly, which, of course, greatly facilitates both its specification and verification.

In light of the above, full verification of Arbitrum's runtime still seems to be a more difficult task compared to a similar undertaking for Stellar, but hopefully it is still within the realm of possibility.

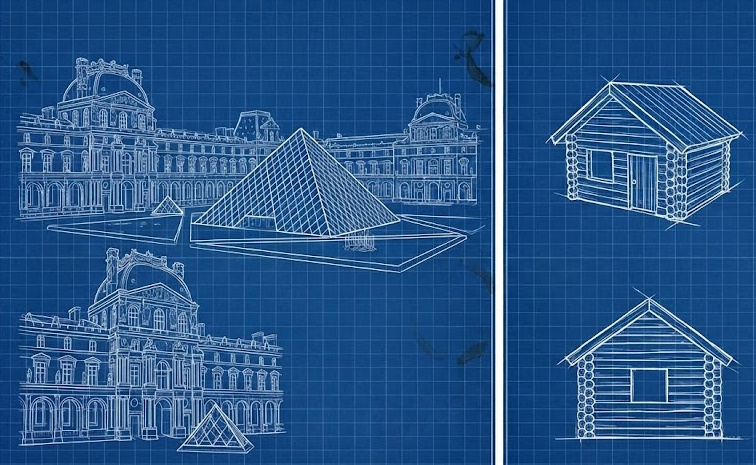

Focusing on the essentials

Let us, however, lay aside plans for world domination for a while and talk about a more narrow perspective. For quite understandable reasons, it is rash to immediately try to apply tools built on truly innovative principles to the construction of palaces. Common sense dictates that we should first practice on small cottages. Even the most favorable of the objects considered, the Stellar core, is no less than the Louvre in this allegory. The question inevitably arises as to how can the work plan be narrowed down to obtain a smoother entry curve in terms of scale? The answer is obvious: it is well known that in terms of total financial damage, the vulnerabilities of the business logic of contracts totally dominate the vulnerabilities of the blockchain platforms themselves. So why not put aside questions of infrastructure reliability for now and try to focus solely on business logic?

By the very nature of DeFi, the business logic of each blockchain must inevitably break down into strictly isolated atomic transactions with narrowly defined interaction semantics corresponding to mostly simple accounting operations. The contracts serving these transactions can thus act as a natural training target for testing new verification technologies. When viewed from this perspective, the overall picture changes only in scale:

- Polkadot Substrate, which does not separate business logic from infrastructure, appears to be the most challenging target by a wide margin. Accounting pallets differ from system pallets only in meaning, and after being assembled into a single monolith, one should not even try to cover them with formal specifications. In such a situation, it is only possible to obtain any worthwhile guarantees of reliability by limiting oneself to verifying Ink! contracts written in a completely self-sufficient manner, relying only on a strictly limited subset of system pallets. This does not completely solve the problem of mixing accounting operations with the entire infrastructure, and such an approach can hardly be called a conventional way of using Substrate, but unfortunately, it still seems to be the only promising one regarding formal verification of business logic.

- Stellar Soroban once again appears to be the benchmark for verifiability. Business logic and infrastructure are strictly separated along the physical boundaries of the WebAssembly sandbox, cross-border interfaces are ridiculously simple, and the consensus mechanism is completely abstracted. The executable contract module consists only of business logic with literally zero overhead.

- Arbitrum Stylus is again somewhere in the middle. They clearly tried to get rid of excess overhead, but unfortunately, the EVM persistence model sets an insurmountable lower limit on complexity.

In this context, the scale of such an undertaking ceases to be intimidating. The relative compactness and isolation of the objects under consideration allows for experimentation with approaches without fear of getting bogged down in details. Work on Soroban contracts can begin immediately after receiving a functioning MVP, and even Polkadot is moving from the category of unthinkable to the category of “not easy, but possible.”

The Silver Bullet

So how does this unusual new tool work? We hope to demonstrate its capabilities soon by using smart contract verification as a testing ground. It consists of three main components:

- The inference compiler (

infc) for the innovative high-level language Inference, combining the semantic transparency of C, a Rust-like syntax more familiar to modern developers, and a unique ingredient which is controlled non-determinism combined with quantifiers for generalizing statements about computations. This language will allow both the source code of the contract itself and its full formal specification to be formulated in a uniform syntax with the expressive power of higher-order logic. - Mechanization of the WebAssembly standard in the interactive theorem prover Rocq, enhanced by a new formalism; a definitional interpreter, proven to be isomorphic to the inductive definition of operational semantics. Using such an interpreter as a basic tactic will effectively turn the interactive Rocq mode into a full-fledged environment for symbolic computation in WebAssembly semantics.

- A mathematical theory, also mechanized in Rocq, that allows any definitive interpreter to be generalized to an entire language of tactics, with which the properties formulated in the specifications of our new paradigm can be proven with an unprecedented level of comfort, completely abstracting away all the insignificant details of the analyzed code.

We hope that, after testing these innovations in the smart contract sandbox, we will be able to scale up our approach in the future to improve the reliability of the platforms themselves. To our understanding, there are no fundamental obstacles to this at present.