Table of Contents

- Introduction

- UniswapX and 1inch Fusion

- 1inch Fusion: The Classic Dutch Auction

- Uniswap X: A Two-Stage, Differentiated Auction

- Learnings

- Monitoring & Data Acquisition

- Seizing the Opportunity: From Research to Revenue

- Become a market leader, not a research team.

Introduction

This blog post is meant to share some of our insights and findings from a completed research project. We were hired to calculate the economic models of the UniswapX protocol from the game-theory perspective in trading. We found the ultimate idea of UniswapX and similar protocols very interesting because it enables owners of substantial capital to participate in the market-making process with less protocol and Liquidity Provider (LP) risks. This blog post is a great place to start for those who have capital and want to use it efficiently through an exchange that does not manage the orderbook itself, but just fills the orders provided by Uniswap.

Having become an integral aspect of the new digital economy, the decentralization of financial services has brought many advantages but, has also introduced several problems. Until recently, these problems burdened anyone who needed to move liquidity from one digital asset to another. For years, ordinary users of decentralized crypto exchanges (DEX) have faced a familiar set of headaches: bots that “sandwich” other people’s swaps; sudden spikes in network load that send transaction fees sky high; unpredictable slippage that renders the quote shown in the swap window largely meaningless. Early generation automated market makers (Uniswap V2 and V3) addressed the problem of passive liquidity provision more than they corrected these inherent flaws in the act of swap execution itself.

This situation began to change meaningfully only with the rise of a radically new paradigm; intent-based swap mechanisms. Unlike the traditional approach, which places responsibility for preparing the transaction on the swap initiator (the services merely sign to release funds if the transaction is acceptable), intent protocols let users abstract away entirely from the details of the prepared transaction and its surrounding conditions. By signing a declaration of intent to swap X tokens of one type for at least Y tokens of another, the initiator delegates every other decision to the service and thanks to smart-contract guarantees this happens in a trustless way: with a sound architecture, neither the service nor the selected counterparty can execute a transaction whose parameters deviate from the user’s declared intent.

Here we compare the two most influential realizations of this architectural idea so far. Uniswap X and 1inch Fusion. Both stand on the solid foundation of a classic Dutch auction, yet they differ in implementation details in a way that is significant enough to be economically interesting.

UniswapX and 1inch Fusion

UniswapX V2 is the current (time the blog is published) actual and deployed on the mainnet version of the protocol.

As usual, the comprehensive documentation about V1 and V2 is available on the Uniswap documentation site.

Let’s begin with a closer look at the conventional workflow whose shortcomings both systems aim to fix. In a standard trade (whether on an exchange or p2p via escrow), the initiator effectively self-services the entire process: they find a source of liquidity with sufficient depth (or several, for larger trades), transfer their tokens into escrow or onto an exchange (paying a network fee the first time), lock in the exchange rate (or abort if it has become unfavorable), and finally, again at their expense, withdraw the proceeds (or the unused input tokens) back to their wallet. Receiving the full amount thus depends on the success of the operation at each liquidity source individually. If an exchange rate slips too far somewhere, the trader has to seek liquidity elsewhere, absorbing sunk costs for the failed attempt. These could include transaction fees, price fluctuations or opportunity costs. Meanwhile, the time gap between choosing a liquidity source and the actual price lock-in inevitably tempts counterparties to manipulate prices for their own profit (MEV). This unfortunate state of affairs raises several pressing questions:

• MEV threat: Can users be protected from bots that predatorily maximize the value extracted from others’ transactions by manipulating execution order?

• Liquidity fragmentation: Can a user be given access to hundreds of different liquidity sources scattered across exchanges and private inventories, while abstracting away the integration complexity behind a simple, cost-efficient operation?

• Sunk-cost risk: Can users avoid paying for transactions that, for whatever reason end up failing?

Both 1inch Fusion and Uniswap X have similar answers to these questions. By reframing the operation as an auction of the swap order among professional executors, present a new alternative. Making counterparties compete for the right to serve the client hits multiple targets at once:

• Protection from failed transactions: In this model the user does not prepare the transaction; they simply sign, at no cost, an instruction for the service to find the best executor for an order with specified parameters.

All network fees and potential losses from failure are internalized into the market spread, which executors minimize under competitive pressure by pricing risk accurately.

• Harnessing MEV for the client: Market makers’ entirely legitimate drive to maximize profit not only comes out of the shadows but also meets a natural check in the form of competition. The order is executed by whoever offers the best spread, and the price promised in the signed contract is fixed before funds leave the user’s wallet, without leaving a temporal window for price manipulation.

• Transparent aggregation of fragmented liquidity: Because the system merely enforces the contract between the parties, it does not require executors to pre-deposit funds to form a common liquidity pool. From the auction’s perspective it doesn’t matter where the tokens come from, as long as they land in the client’s wallet before the deadline. This allows executors to effectively resell all liquidity available in the market through a single window.

It’s hard not to notice that while this economic model dramatically simplifies the swap for the initiator, it necessarily makes life more complex for the executors. Compared with classic exchanges — where participation can be as simple as depositing liquidity, posting a price, and passively waiting for buyers, the auction scheme forces participants on the execution side to make many more decisions under tight deadlines. Automation here is non-negotiable. It creates a state of constant readiness with hard response times which leaves a human with no chance to beat the robots. Below we dive into which economic decisions compel such automation on both platforms.

Although 1inch Fusion and Uniswap X implement the same core idea schematically, they differ quite substantially in the design of their mechanisms. We’ll examine them separately and then compare them, starting with 1inch.

1inch Fusion: The Classic Dutch Auction

This protocol embodies the “simple is elegant” principle. Here we break down the process of a transaction using 1inch Fusion. An order is configured by only three numbers (start price, reserve price, and auction duration), which is then listed in a continuous auction that begins at the most favorable price for the client and then linearly drifts toward the pessimistic reserve price over the auction’s duration. The auction (in the current version) is closed: executors must register and pass KYC. To act on a listed order, a participant executes the user-signed instruction to transfer tokens from the user’s wallet into a special bi-directional escrow that records the exact timestamp of its on-chain inclusion. The first to do so wins the auction; the resulting price is computed deterministically from the order parameters and the escrow’s recorded opening time. From that moment the executor enjoys an exclusivity period, during which they can fulfill their side of the deal by funding the opposite direction of the escrow with the required amount of the tokens the client wants to receive. The final step is closing the escrow, which simultaneously releases the frozen funds in both directions. This final step is also paid for by the executor before the exclusivity expires.

The concrete timeframes of auction and exclusivity periods are not defined in the protocol and are subject to service provider. At the moment of writing in both 1inch advertisements and practice the vast majority of swaps complete within 5 minutes.

If something goes wrong and the executor stops midway after freezing the user’s funds, then once the exclusivity period ends the act of closing the escrow becomes public: By paying the network fee, any wallet can either return the user’s tokens in full (if the counter-escrow was never sufficiently funded) or complete the swap (if it was funded but the executor couldn’t close the escrow for technical reasons). To make public closure economically meaningful, the protocol requires auction participants to bond a small amount of their own funds in the escrow alongside freezing the user’s tokens — an amount sufficient to cover network fees. These funds are always paid to whoever signs the escrow closure; during exclusivity they are returned to the executor; after exclusivity they become a reward for the party that completes or cancels the swap. Through this method it allows for fulfilling the client’s needs in a way that remains transparent to them.

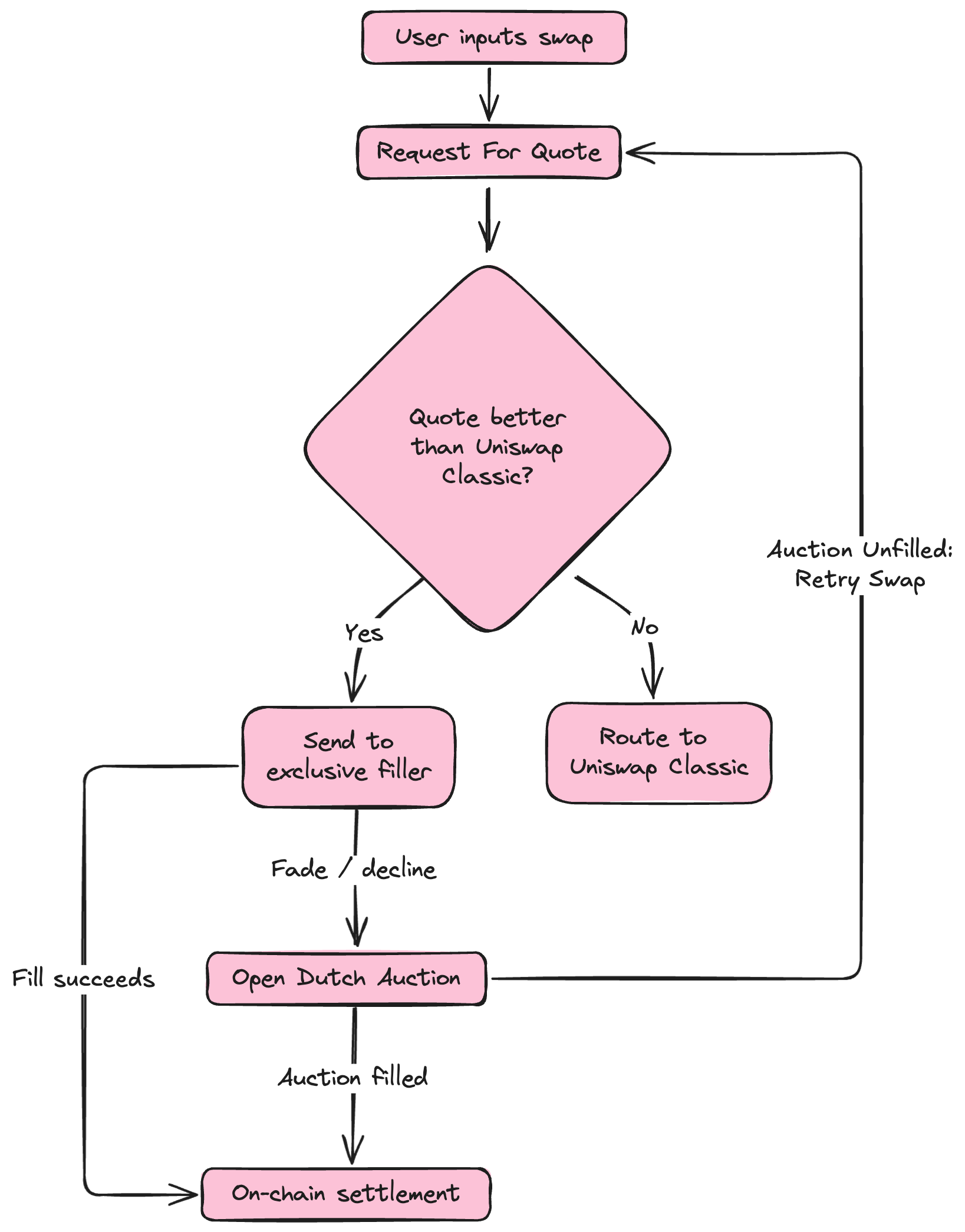

Uniswap X: A Two-Stage, Differentiated Auction

This design is somewhat more complex, but for good reasons. The protocol splits executors into two unequal groups that perform actions at different stages. The first group to interact with the client’s order are registered, KYC-verified Quoters, whose work actually starts before the user signs anything. When the user selects a direction of their trade and types the desired amount (either what they want to sell or what they want to buy) into the form, a draft of the order is broadcast to all Quoters serving that trade direction. Each Quoter is expected to respond very quickly (within roughly half a second) with a quote — i.e., the complementary amount of tokens. If the client sells a fixed quantity of their tokens, the quote is the price the executor is willing to pay. If instead the client wants to buy a fixed quantity of the other token, the quote is the price at which the executor is willing to sell those tokens.

In both cases, Quoters compete to offer the most favorable quote for the client. The platform selects a winner, shows that quote in the swap form, and invites the user to sign a payment instruction. From that moment, the winning Quoter is considered to have taken on an obligation to honor the quote provided the user signs before a countdown timer (30 seconds) expires. This stage is exclusive to the winning Quoter. Execution of the signed instruction is also given a fixed, on-chain deadline; upon expiry, the overdue obligation is deemed breached and the client’s order is considered to have failed the exclusive stage. A Quoter who does not keep their promise to execute the order in time is penalized with a temporary suspension from quoting new orders.

This initial cooldown period which uniswap calls “fading” begins at 15 minutes and increases exponentially with each failure in succession. Though, after each fade ends even one successful fulfillment of order resets penalty escalation.

Only orders abandoned by their winning Quoters proceed to the second stage, which is a more archetypal Dutch auction much like the 1inch Fusion mechanism described above. The most economically significant difference here is that Uniswap X’s second stage is open to the public without registration. From the end of exclusivity period until the auction reaches the client’s reserve price, anyone can act as the executor (a Filler), which should further compress the final spread by intensifying competition.

This added complexity is not wasted: by forcing first-stage Quoters to shoulder an obligation to honor the price shown to the user even before the user decides to swap, Uniswap X creates a valuable user-experience feature that would be hard to reproduce otherwise. By comparison, under 1inch Fusion the exchange rate visible to the client at signing time is merely an approximate, non-binding estimate by the platform; the final price is determined somewhere between the start and reserve prices during the (sometimes lengthy) auction.

Under Uniswap X, in the overwhelming majority of cases the user decides to sign while looking at the actual amounts that will be sent and received almost immediately after pressing “Approve and swap”. That’s because instances of a Quoter failing to complete an order are relatively rare; the open Dutch auction plays the role of a safety net rather than the backbone of the system.

A qualitative economic analysis suggests that this undeniably useful feature is not free for the user. The extra obligations and risks shouldered by Quoters in Uniswap X naturally push them toward more conservative expectations of execution profitability for the same nominal spreads. One should expect that for swaps involving more volatile tokens (or during volatile periods for otherwise stable pairs), the simplicity of the classic Dutch auction in 1inch Fusion will, on average, extract a smaller share of value from client orders.

Learnings

Our practical experience gained while economically advising a startup currently building an automated market maker (bot) for Uniswap X, and during a hackathon prototyping cross-chain trading functionality on 1inch Fusion can be summarized as follows:

Regardless of platform choice, an automated market maker for intent-based protocols is a mechanically non-trivial artifact whose success depends not only on solving the technical integration tasks with the platform’s services, but also on adopting a strategy that addresses two interrelated, economically substantial points:

First, the bot’s effectiveness depends directly on its ability to price quotes quickly and accurately for the pairs it serves, and to adapt its pricing algorithms promptly to changing market conditions. The choice of primary signals used by the algorithm to determine the most advantageous quote is critical. Natural candidates include public data from centralized exchanges mark prices for the trading pair and raw spot order book data. These inputs enable quote-estimation algorithms that respond promptly to market dynamics.

Second, any serious optimization of the bot’s profitability is impossible without close attention to efficient liquidity reserve management. Although intent-based protocols allow executors to draw missing liquidity from virtually any source available in the market at any time, maintaining adequate operational reserves on the bot’s own wallets can substantially reduce transaction costs.

Since the model of protocols for addressing the points addressed above has to be algorithmic, i.e., delegating financial decisions to a program, the problem of access to data for market analysis becomes particularly acute. On traditional exchanges, trading participants are naturally divided into three main groups, depending on how they obtain the information on which their strategy is based. Buy and hold investors learn market news from newspapers or other traditional forms of media. Day traders sit in front of several monitors displaying Nansen, Arkham, and Etherscan information panels. Finally, High Frequency Trading (HFT) robots listen to the raw APIs of trading platforms, filtering useful signals from gigabytes of digital noise in real time. In terms of the requirements for market data sources, the automation of order execution for intent-based protocols occupies a middle ground between day trading and HFT. On the one hand, we can no longer place full responsibility for financial decisions on humans, but on the other hand, trading takes place at a fairly calm pace by modern automation standards. The tightest timing in the protocols we reviewed is half a second (500ms) for a quote in Uniswap X, while all other periods are measured in blocks (12 seconds each for Ethereum). Here, unlike with HFT, the speed of reaction to events does not create any significant engineering problems. Since 12 seconds is a rather forgiving time frame for such systems, it would take severe errors in design or execution to fail these requirements.

Accordingly, the need for accuracy in determining exchange quotes and the optimization of liquidity management present themselves in the auction model. The bots who consistently offer a better price than competitors while remaining profitable take all the revenue from the market.

For the economic tasks at hand, due to such intermediate position of data requirements between day trading and HFT, the usual sources of data create a number of inconveniences. Classic information panels (Nansen, Arkham, and Etherscan), which are mainly aimed at day traders, offer a fairly limited set of market activity projections. Their unquestionable convenience in terms of supporting specific economic decisions in a rapidly changing market environment, unfortunately, does not translate well into supporting the detailed statistical research required to refine the parameters of the algorithm. The need to filter and aggregate data sets that are too large for manual processing makes the use of template GUI representations extremely impractical.

On the other hand, using “raw” blockchain infrastructure APIs and trading platforms, while providing complete freedom of automation, immediately turns any statistical research into a separate engineering task of searching through haystacks for needles. The easiest to access but perhaps also one of the more tedious of the tools that can be used is Etherscan. Etherscan provides a lot of data for transactions, wallets and contracts but navigating it without knowing ahead of time precisely which contract addresses are which or “who is who” can be a frustrating experience. The haystack being the vast amount of information available whereas the needle would be the precise details which we are searching for. In our context it is better purposed as a way to see very precise data such as the transactions of a specific Uniswap X filler. Therefore to avoid this engineering task, before reaching an economist’s desk, the data will inevitably have to pass through the hands of a competent data scientist capable of extracting grains of useful information from the mountains of digital slag spewing out of low-level APIs. Fortunately, thanks to the existence of the Dune platform, this problem can be partially avoided.

Monitoring & Data Acquisition

This is where the Dune platform emerges as a methodological “sweet spot,” uniquely suited to the needs of intent protocol architects. It effectively splits the problem in two: the platform itself handles the monumental engineering task of data ingestion, decoding, and structuring, while the analyst retains the full, granular power of querying this refined dataset.

Dune lets anyone create both public and private dashboards which on the surface utilizes on-chain transaction data for data visualization. First we will focus on the surface level before we dive deeper into the utility of its mechanisms.

During our research phase there were very few public dashboards through which we could see and track the activity of Uniswap X fillers easily, in fact there was only a single reliable dashboard at the time!

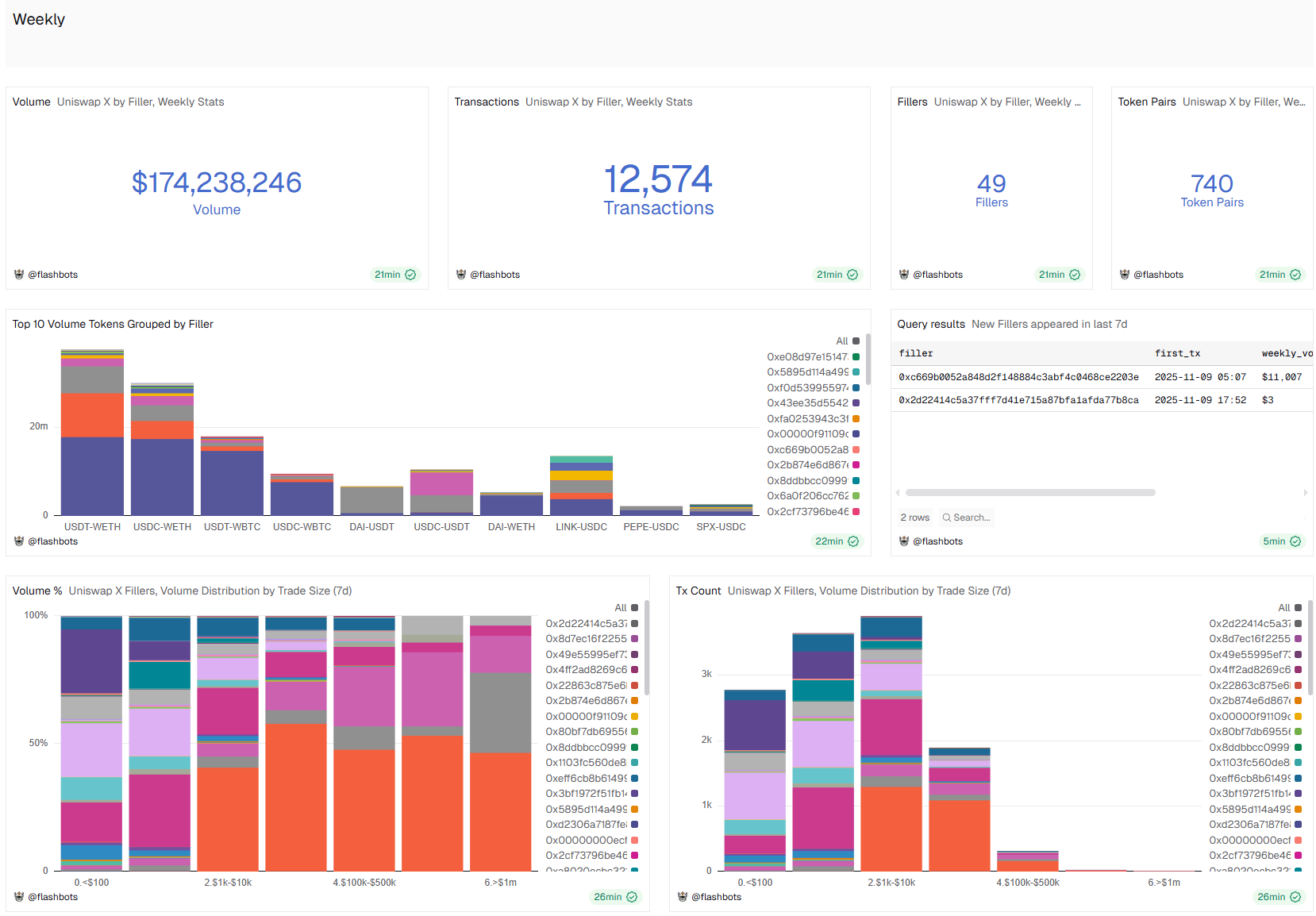

The Uniswap X dashboard by @flashbots lists not only the different active fillers but also vital information such as volume, order size, fillers, transaction hashes and more.

This dashboard might be discontinued or no longer up-to-date

Let’s take a look at some of the publicly available data here. There are two views by default, the top section shows information based on Weekly statistics, the lower section shows All time data.

For now let’s focus on the Weekly area.

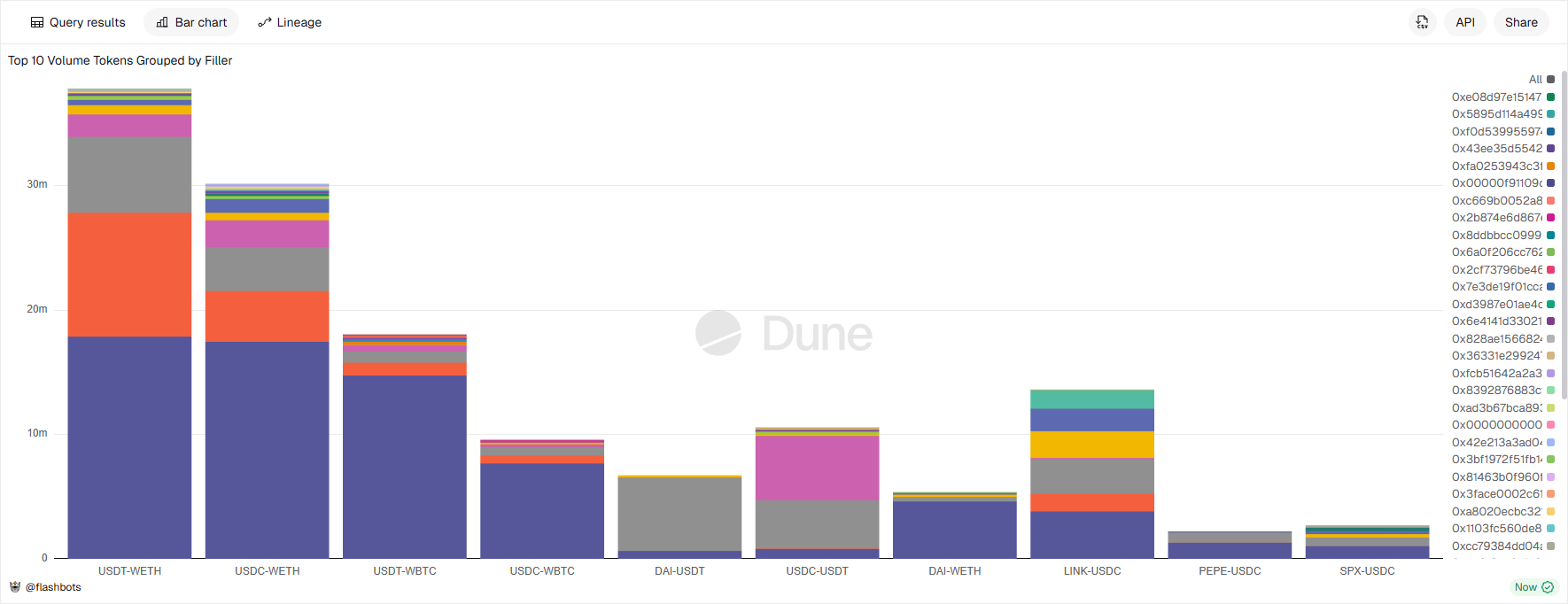

The most notable query that helps us get a better understanding of what kind of trades (and their direction) is the Top 10 Volume Tokens Grouped by Filler query. This not only shows us the top wallets (fillers) but we can clearly see that the trades with the most volume occur between the USDC & WETH (wrapped Ethereum) pair.

Wrapped Ethereum (wETH) is an ERC-20 token that represents Ethereum (ETH) on a 1:1 basis, making it compatible with decentralized finance (DeFi) applications and other ERC-20 compliant platforms. While ETH is the native currency of the Ethereum blockchain, it is not an ERC-20 token and cannot be used in many dApps.

Although it is quite a useful dashboard, in its current state it does not meet all the requirements of a sophisticated automated market maker (bot) for Uniswap X. Basic metrics such as estimated ROI of fillers, transaction costs, portfolio history & allocation are not easily available or calculated through this dashboard. When abstracting towards even more complex concepts such as risk management, liquidity sourcing and performance analytics, a more meticulously refined approach is required.

Dune’s server-side SQL model provides a “Goldilocks Zone” for data access. It offers a level of abstraction that is:

- Higher than Raw APIs: Analysts don’t need to decode hex data, reconcile token decimals, or build complex indexing pipelines. The data is already cleaned, structured, and presented in relational tables like erc20.transfers or dex.trades.

- Lower and Fuller than GUI Dashboards: Unlike the pre-packaged views of Nansen or Arkham, Dune provides direct access to the underlying dataset. There is no artificial limitation on the questions one can ask. An analyst can calculate a custom fee volatility metric, correlate liquidity provision across three different protocols, or model the profitability of a novel MEV strategy all within a single SQL query.

This capability is not merely a convenience; it is a fundamental enabler for the economic design of intent-based systems. The core challenge for these protocols shifts from pure execution speed to economic optimization. The profitability of a solver, and thus the health of the entire network, hinges on their ability to:

- Precisely Price Risks and Opportunities: A solver needs to know more than just the current spot price. It must model the probability of a competing solver finding a better route, the likelihood of a large swap moving the market in the next block, and the implicit cost of failing to fill an order. This requires complex, multi-faceted queries that join data from DEXs, lending markets, and bridge transactions.

- Optimize Liquidity Sourcing: The “winner-takes-most” dynamic of auction-based models means that marginal improvements in liquidity sourcing are paramount. Solvers must analyze fragmented liquidity across pools and chains, model gas costs, and identify arbitrage opportunities that can be bundled with user intents to offer more competitive quotes. This is a integrative problem ill-suited for static dashboards but perfectly suited for exploratory SQL analysis on a dataset like Dune’s.

- Conduct Post-Mortem and Competitive Analysis: Why was a specific order won by a competitor? Was their quote abnormally high, suggesting a novel routing strategy? By replaying market conditions for any past block and querying the on-chain activity of competing solvers, protocols can reverse-engineer successful strategies and identify weaknesses in their own models. This forensic capability is native to Dune’s historical data access.

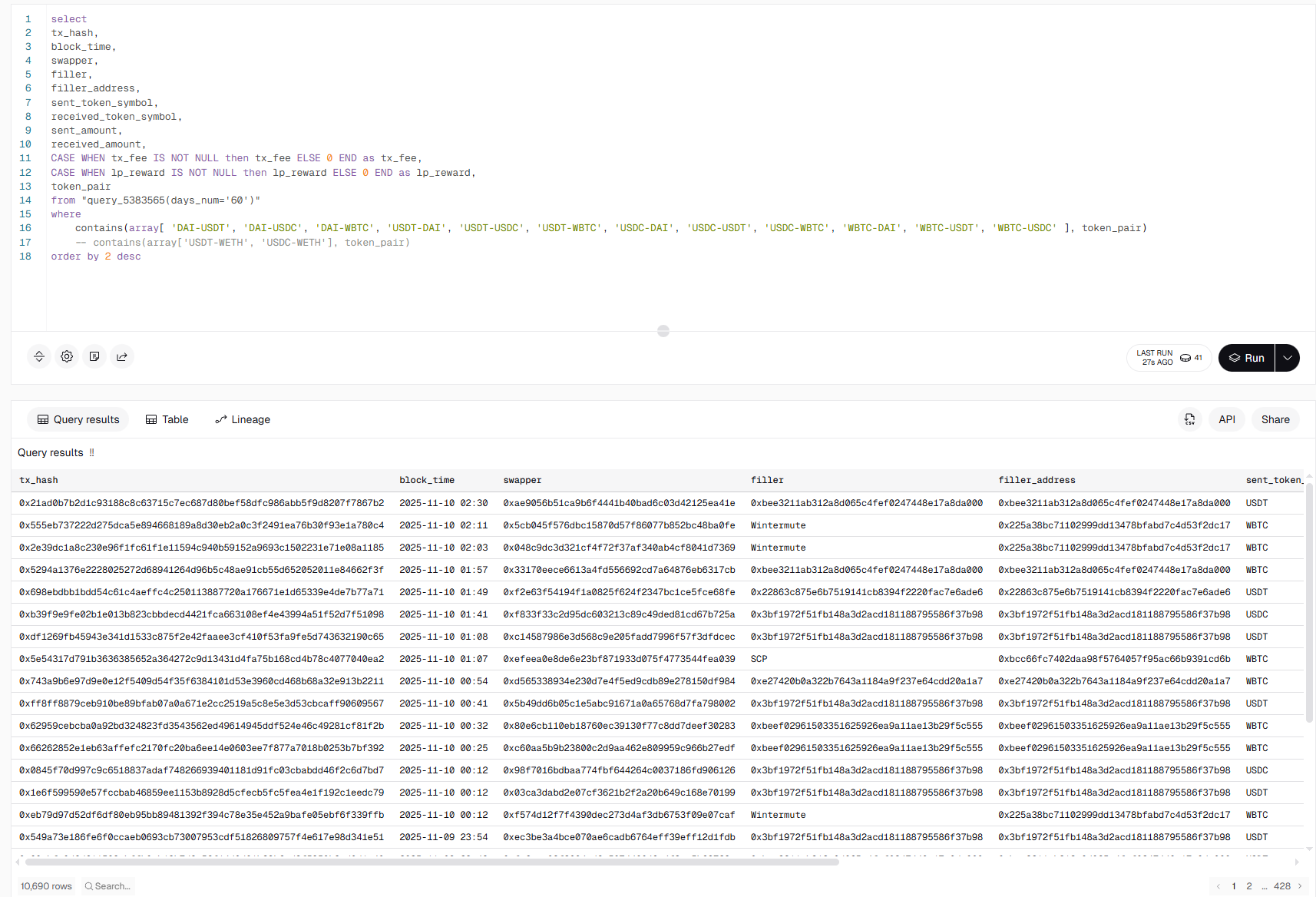

In essence, Dune acts as a computational substrate for economic R&D. It allows small teams of researchers and developers to perform the kind of deep, quantitative market analysis that was previously the exclusive domain of large, well funded trading firms with proprietary data pipelines. To illustrate the power and convenience of Dune’s server-side SQL methodology, we can point, for example, at the main SQL query we have used for aggregation of Uniswap X transactions for ROI analysis (called through this wrapper for parametrization and filtering). Let’s deconstruct it to highlight the meaningful parts that would be extremely difficult or impossible to achieve with standard GUI dashboards or raw APIs.

The Query Parts & Their Significance

Part A: The get_transfers Common Table Expression (CTE) - Unified Token & Native ETH Transfer Handling

WITH

get_transfers AS (

SELECT ... FROM erc20_ethereum.evt_Transfer ...

UNION ALL

SELECT ... FROM ethereum.traces ...

)

- What it does: Creates a unified view of all token transfers (ERC-20) and native ETH transfers for each transaction. This is crucial because economic analysis must consider both asset types.

- The Convenience Illustrated: Automatic decoding of raw blockchain data.

- With Raw APIs: You would need to:

- Fetch all transaction receipts and decode hex-encoded log data using Application Binary Interface (ABI) specifications to identify ERC-20 transfers.

- Separately parse

ethereum.tracesforCALLoperations withvalueto find native ETH movements. - Manually reconcile the different data structures into a single dataset.

- On Dune: The

erc20_ethereum.evt_Transferandethereum.tracestables are pre-decoded and standardized. The complex engineering of data normalization is already done.

- With Raw APIs: You would need to:

Part B: The logs CTE - Protocol Event Aggregation

logs AS (

SELECT * FROM uniswap_ethereum.V2DutchOrderReactor_evt_Fill ...

UNION ALL

SELECT * FROM uniswap_ethereum.ExclusiveDutchOrderReactor_evt_Fill ...

)

- What it does: Aggregates

Fillevents from two different versions of the Uniswap X protocol smart contracts. - The Convenience Illustrated: Abstracted smart contract complexity and versioning.

- With a GUI Dashboard: A platform like Nansen might show “Uniswap Volume” but would almost certainly not expose a specific “Filler Profitability” view, let alone one that seamlessly combines two different contract versions.

- On Dune: The specific, low-level events are readily available in human-readable tables. The analyst can trivially combine them to get a complete picture of protocol activity without knowing the specific contract addresses or ABI details.

Part C: The txs_with_evt_fill CTE - Enriching Transactions with Labels and Prices

JOIN ethereum.transactions tx ON x.evt_tx_hash = tx.hash

LEFT JOIN prices.usd pu ON ... -- For TX fee USD value

LEFT JOIN query_2812729 labels ON x.filler = labels.address -- For Filler labels

- What it does: Joins the core fill events with transaction data (to get gas fees), real-time price feeds (to value those fees in USD), and a labels table (to humanize filler addresses).

- The Convenience Illustrated: Seamless, on-the-fly data enrichment.

- With Raw APIs: Calculating the USD cost of a transaction fee would require:

- Fetching historical ETH price data from another API at the exact block timestamp.

- Manually joining this data.

- The Labeling Problem: Identifying “who” a filler is (e.g., “janitooor.eth” or “Uniswap Team”) is a core feature of GUI platforms like Arkham. On Dune, this is democratized. The

query_2812729is a public, community-maintained labels list that anyone can use, fork, or contribute to. This turns a proprietary “secret sauce” into a collaborative, public good.

- With Raw APIs: Calculating the USD cost of a transaction fee would require:

Part D: The get_swapper_txs CTE & Subsequent Aggregations - Complex Business Logic

CASE WHEN transfers."to" = fill.swapper THEN true ... END as to_swapper

...

CASE transfers."to" WHEN 0x000000fee13a103A10D593b9AE06b3e05F2E7E1c THEN true ... END as to_uniswap

- What it does: This is the core of the economic logic. It categorizes every token flow in the transaction:

- Was it sent from the swapper? (This is the input)

- Was it sent to the swapper? (This is the output)

- Was it sent to a known Uniswap fee address? (This is the protocol fee/LP reward)

- The Convenience Illustrated: Full expressibility to encode custom economic models.

- With a GUI Dashboard: You are locked into the platform’s predefined metrics (e.g., “Volume,” “TVL”). You could not create a custom metric for “Filler Net Profit” that subtracts protocol fees and gas costs from their gross spread.

- On Dune: The analyst defines the business logic directly in SQL. The

CASEstatements and subsequentsent_data,received_data, anduniswap_fee_dataCTEs are a direct implementation of their unique economic model for the protocol.

Part E: The Wrapper Query - Parameterization and Filtering

from "query_5383565(days_num='60')"

where contains(array[ 'DAI-USDT', 'DAI-USDC' ... ], token_pair)

- What it does: The main, complex query is saved as a reusable “data source.” This wrapper query calls it with a parameter (

days_num='60') and filters the results for specific token pairs. - The Convenience Illustrated: Composability and parameterization.

- This turns a complex, one-off analysis into a reusable tool. An analyst can now trivially run the same deep analysis for different time periods or asset pairs without rewriting the core logic. This modularity is a cornerstone of efficient research.

Conclusion: The “Server-Side SQL” Value Proposition

This single query performs a task that sits perfectly in the “intermediate position” described above. It is far too complex and specific for a pre-built GUI dashboard, which wouldn’t offer this exact view of filler economics. At the same time, it would be a multi-week engineering project using raw APIs, requiring a dedicated data engineer to build and maintain the pipelines for data decoding, price feeds, and entity labeling.

On Dune, this complexity can be subdued by a single analyst.

The methodology allows the researcher to focus entirely on the economic logic (CASE statements, JOIN conditions, SUM aggregations) rather than the data engineering plumbing (decoding logs, fetching prices, managing decimals). This is the ultimate convenience of server-side SQL: it turns deep, custom, protocol-level economic research from an infrastructure problem into a query problem. Due to the open nature of blockchains there is a lot of data that is readily available, however actually parsing and making sense of it can be more difficult.

Throughout our research phase we used and created several resources to help monitor the transactions and activities of fillers on Uniswap X specifically.

For this specific research our client wanted to focus exclusively on transactions occurring on Ethereum mainnet. Since we can not share the exact mathematical modeling, datasets and fully applied results of our research, we instead focused on explaining some the methods and reasons that are important when monitoring & acquiring data of this kind. We hope this has been an insightful peek into the complexities of building and researching such systems.

Seizing the Opportunity: From Research to Revenue

Now that we’ve explained some of the complexities of operating an efficient automated market making bot from the architectural perspective let’s briefly consider the financial opportunities that it enables with proper guidance and support. Understanding these complex systems and actually utilizing them efficiently for financial gain are entirely different.

Although the total number of swaps seem to have increased from our initial time of research, the number of unique fillers has not increased proportionally.

This means existing, sophisticated fillers are capturing expanding profits with minimal competition.

It’s not just the methods of acquiring information that adds complexity to compete with on-chain market makers. There are several things to consider such as budget, portfolio management and infrastructure requirements to actually deploy such an efficient market making bot.

Through our research and experience we can alleviate the high barriers of entry that exist when wanting to become a participant in market making platforms such as Uniswap X.

Our team will help steer you in the right direction through research & consulting work. We’ve done the research and built the tools to help our clients achieve their vision.

As we have demonstrated, the barrier to entry isn’t capital. It’s the immense technical and economic complexity. A successful market making operation requires:

- Accurate Pricing: Sub-second, real-time risk and pricing algorithms.

- Optimized Liquidity: A strategy to source liquidity efficiently from various sources.

- Resilient Infrastructure: High availability systems that can respond to quotes in under 500ms, 24/7.

- Continous R&D: Deep, continuous data analysis to model competitor strategies.

Building this from scratch is a long and costly R&D challenge. We have already completed the R&D.

We don’t offer a one size fits all bot. We partner with funds and high-capital players to design, build, and deploy a custom market-making solution that leverages our proprietary research.

You provide the capital and strategic vision, we provide the expert team to build your engine.

Our partnership is designed to get you to market in a fraction of the time and cost it would take to start from zero. We work with you to build:

- Custom Strategies: Design, model, and deploy proprietary algorithms tailored to your specific risk appetite and capital base.

- Bespoke Data & Analytics: Build and deploy the proprietary, real-time dashboards and data pipelines you need to gain a true competitive edge beyond public queries.

- Custom Portfolio Automation: The automated tools required to efficiently manage your liquidity reserves, hedge exposure, and rebalance assets.

Become a market leader, not a research team.

By building on our completed research, you can avoid the intensive R&D phase required and move directly to building your institutional grade system.

We are a trusted research and development team for top-tier Web3 protocols and bring this same level of institutional grade expertise to our market-making clients.

The window of opportunity is open now, but it won’t be for long. Don’t spend your budget on the research phase.

Contact us today for a private consultation to discuss building your own custom, high performance market making bot.

Discuss the blog blog with others: